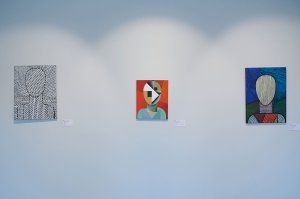

Alexander Yulikov’s solo exhibition at GUM-Red-Line Gallery is exceptional because it serves as a first-time retrospective of over half a century of the artist’s work. The exhibition opens with “Self-Portrait” (1958) which was created when the author was a student at the Moscow Central Art School and concludes with pieces currently under production. Most of Yulikov’s self-portraits were never exhibited despite the popularity of the artist. Some of the pieces were created specifically for this exhibition. “Heads” represent a recurring theme in the artist’s works for over 65 years. Never before was this motive displayed in such a gradual, progressive way. Yulikov’s 2023 jubilee exhibition at Tretyakov Gallery was dedicated particularly to his abstract works.

Alexander Yulikov (b. 1943) is a non-conformist, participant in group exhibitions by independent artists of the Brezhnev period: Izmailovo Forest Part (1974), VDNH Beekeeping Pavilion (1975) and VDNH Culture Pavilion (1975), first art exhibition on Malaya Gruzinskaya St. (1977), as well as 1970s apartment exhibitions.

Alexander Yulikov is renowned as one of the few minimalist and postminimalist artists of the USSR and Russia. In 2020, he was awarded the Barnett and Annalee Newman Foundation Award in recognition of his “individuality and independence.” Works by Yulikov are presented in the collection of the Jewish Museum (New York), State Tretyakov Gallery (Moscow), State Russian Museum (St. Petersburg), MMOMA (Moscow), Zimmerli Art Museum at Rutgers University (USA), etc.

Alexander Yulikov’s solo exhibition “Heads” at GUM-Red-Line Gallery includes over 30 artworks dating from 1958 to 2024.

The exhibition will be open from May 22 to August 23, 2024.

Curator: Mikhail Sidlin.

Artist:

Alexander Yulikov

SPATIAL SYSTEMS

Alexander Yulikov’s procedural art

Mikhail Sidlin

We must think of spaces as a universal force that determines the possibility for things to come together. Spaces are not storages of things or an abstract value that things possess when brought together.

Maurice Merleau-Pont. Space

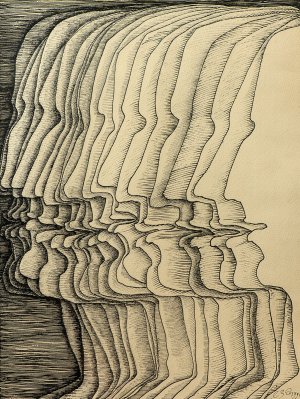

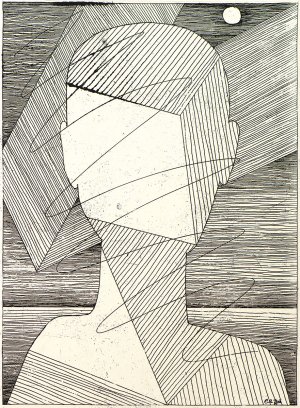

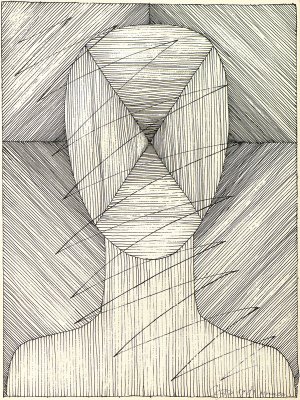

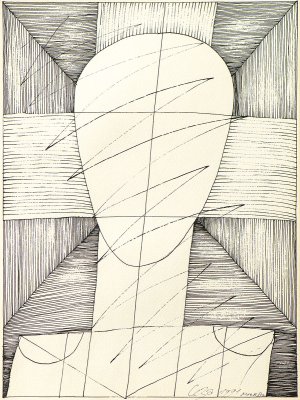

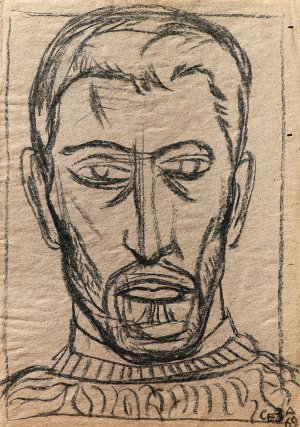

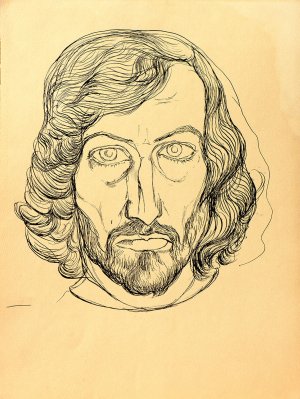

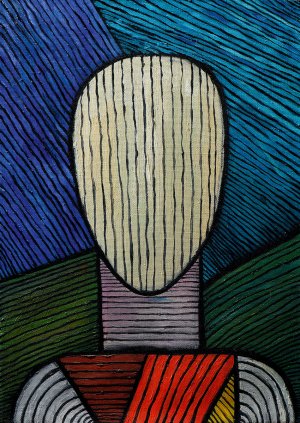

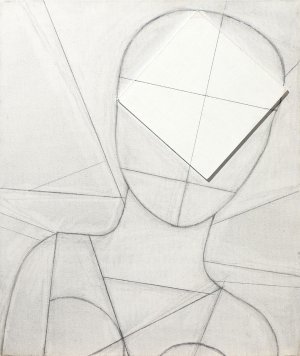

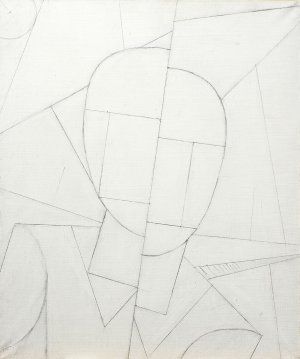

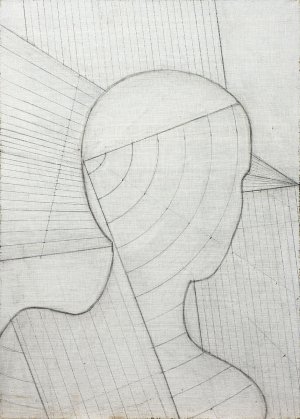

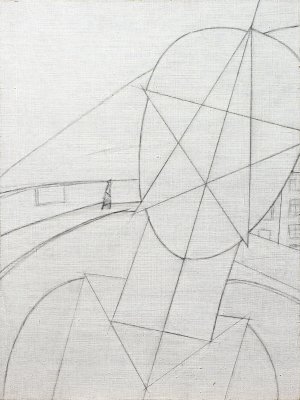

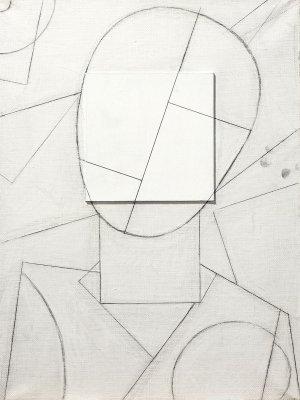

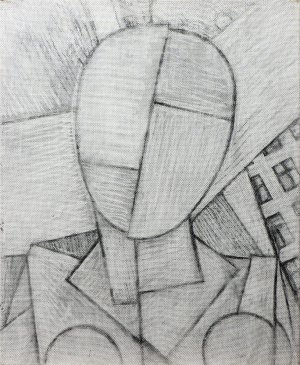

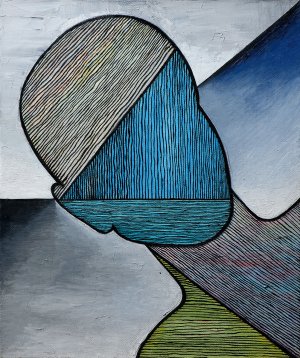

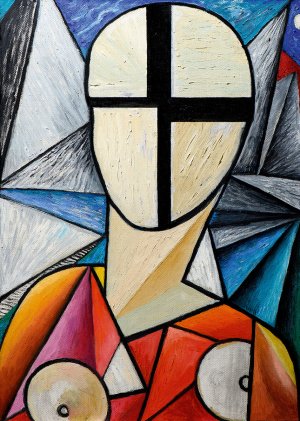

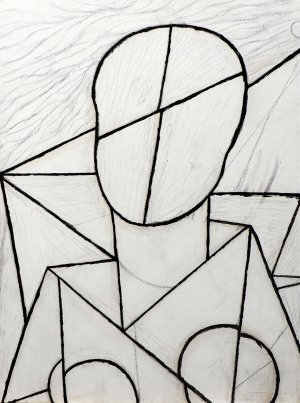

Heads are a notable feature in the art of Alexander Yulikov. Two distinct periods can be identified concerning this motive: firstly, circa 1957-72 — a period of experimentation when the artist tried out various modernist styles; secondly, around 1984-2024 — the postminimalist period when the artist united general corporeal forms with abstractions.

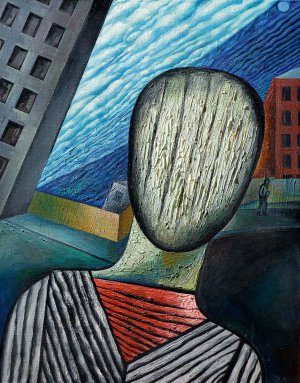

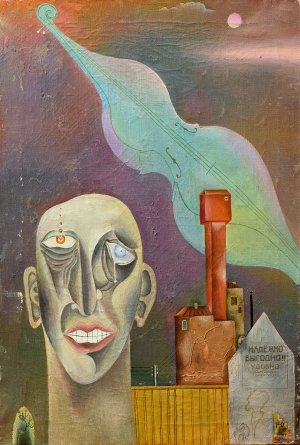

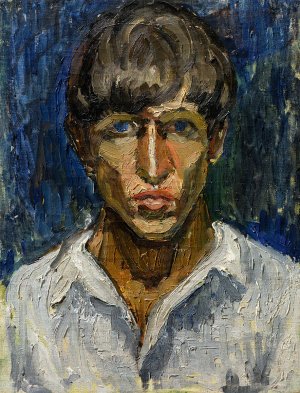

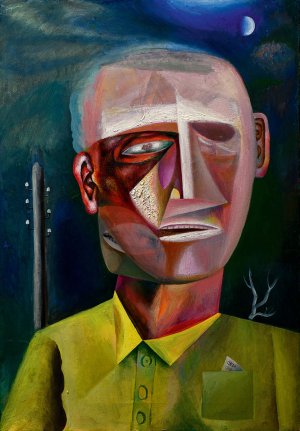

The period of experimentation saw Yulikov attempting modernist techniques from various “toolboxes.” For example, “Self-Portrait” (1958) showcases the young artist’s focus on postimpressionism. The “Man’s Portrait” (1963) represents a person with three eyes, two noses, and three rows of teeth, revealing the impact of Picasso circa the period when the master worked on “Guernica”.

Yulikov created expressionist works in a wide selection of styles up to the late 1960s, i.e. during his studies over an extended period at several institutions (Moscow Secondary Art School, Stroganov Academy, Polygraphy Institute).

Soviet education did not teach any of this. The novelty came from two sources. First of all, libraries/museums. Yulikov was always a well-read artist. He was born into a Moscow family of scholars. To this day, Yulikov keeps editions in various languages in his personal library, ranging from Italian (a rare catalogue from the first grand international exhibition of Italian futurists that was hosted in 1912 by the Bernheim Gallery 1*) to English (catalogue from one of the first pop art exhibition hosted in 1965 at the Worcester Art Museum) 2* . The main quality of these books relates not to their texts but rather to their illustrations, both in color and black-and-white. They served to nurture the Soviet student’s affection for modernist art. Three national exhibitions (American, French, and British) presented in Moscow in the late 1950s and early 1960s opened the floodgates, exposing a new generation of artists to Western art.

The intellectuals and fashionistas of that time experienced a lack of information and ideological pressure, so they learned to value all sources of current information. Having studied at three leading art institutions of the Soviet Union by the late 1960s, Yulikov was personally acquainted with artists from two generations: his students and their friends, on one side, and their parents and teachers, on the other hand. This circle of several hundred people represented the foundation of the Moscow art community. Yulikov was friends with a wide range of individuals, from the “academic” Bubnov clan to the always disfavored Oleg Grigoriev5*.

The “Iron Curtain” proved to be full of holes. Everything that was squeezed out, stricken out, or forgotten from official art history could be learned from books or friends. Some things demanded a personal period of trial and error. Some of Yulikov’s early works of the late 1950s — early 1960s display the influence of Vladimir Pyatnitsky6* and his milieu. See, for example, “Reliable. Useful. Comfortable” (1962). The motive of the service shirt is presented in two 1968 pieces (“Man’s Portrait” and “Red Cap Figure”). It was inspired by the army service of Kosolapov7* who was a childhood friend of Yulikov. Notably, neither image could be deemed to be a portrait. The motive of the red cap is a reference to Harlequin’s tricks (or, perhaps, the first representation of a full-frontal portrait in the history of the Italian Renaissance. i.e. the “Portrait of a Man with a Medal of Cosimo the Elder” by Sandro Botticelli, c. 1474—1475). The earliest heads created by Yulikov reveal the impact of museum/library-sourced inspiration and real-life experiences.

Yulikov’s heads have little to do with commercial portraits. The artist rarely showcases his models. The images do not correlate with actual people. Even if there is any relation to be gleaned, it’s usually by association. Details, not recognition. Only Yulikov’s earliest works, including his school self-portraits and the 1950s portraits of his parents, could be termed as actual portraits.

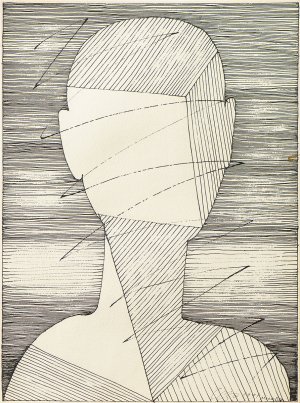

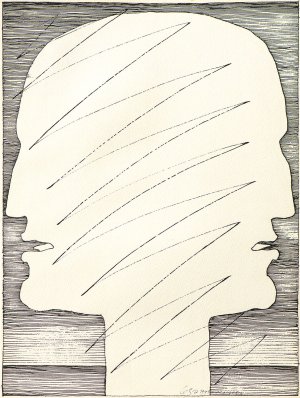

A head represents the most general idea of a person. Yulikov comes to the idea of “a person in general” gradually, by moving from his own face to the face as a marker. His first school self-portrait (1957) reveals a recognizable face with obvious individual traits. However, his next self-portrait (1958) is a parsuna, an image with no emotional accents, much more similar to Fayum mummy portraits or sacred icons in character. Several works from the late 1960s — early 1970s demonstrate that this shift to the face as a marker was not a straightforward process but rather consistent variations of a single theme.

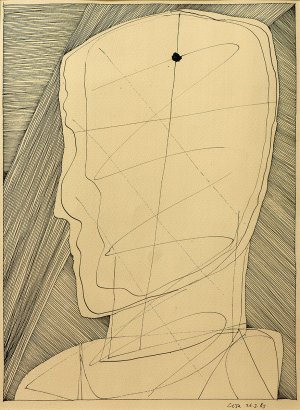

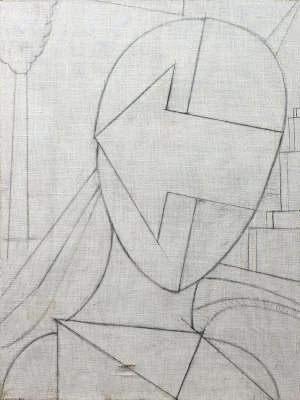

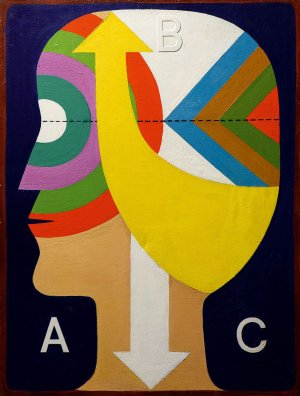

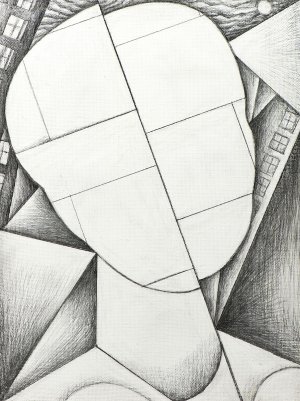

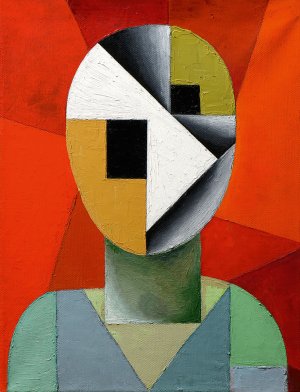

In the “Torso” (1965), Yulikov showcases a person as a combination of shapes, i.e. the artist deconstructs the body. In the “Face” (1965), the geometric technique remains, yet Yulikov also focuses on the eyes as a key feature that makes a face a face. Still no individualization, though. In the “Head” (1966), Yulikov divides the image into several colorful corners that are presented in large, differently aligned brushstrokes, resulting in a lively cubist profile. On the other hand, “Profile А В С” (1972) is a deliberately flat painting. Only the three letters protrude beyond the painted cardboard. Here the face is reduced to a part of a symbolic system, in this case, an ABC-book. These four works showcase a variety of styles that the artist mastered in the first 15 years of his conscientious work.

Mel Bochner noted solipsism as a trait of minimalist art 3*. Yulikov’s earliest attempts at painting heads forced the artist to move away from representing people. Yulikov is usually deemed to be a minimalist. However, “minimalism” does not exactly apply to either his early or, indeed, later works. The earliest works can best be described as experimental postwar modernism while the later works are more “serial” or “systematic” in nature. It’s more apt to place Yulikov’s art in the context of postminimalism. However, this is not the American postminimalist art school (a rather confined school that can be deemed a contemporary of minimalism, not its successor). In the case of Yulikov, minimalism, similar to pop art or conceptual art, serves as a point on the route of the wide-ranging international shift from modernism to postmodernism.

Yulikov’s works lie outside of the heroic modernism. He is also not a socially critical artist, be it in the form of “smearing reality” that is a feature of the “Lianozovo” school or in the form of a critique of normality that is characteristic of Sots Art and “Moscow Romantic conceptualism.” Yulikov develops his unique style within the international field of abstraction and does not directly follow any of its known variants. Yulikov is closest to minimal art. Out of all concepts of minimalist art, Yulikov is best described by a phrase coined by Lawrence Alloway who suggested that “serial” art is a “continuous stream” of works and “internal” development of its various parts 4*

. Serial art in classic painting refers to the development of a single theme. For example, the Galerie Médicis at the Louvre presented the life of a queen as a series of events allegorically represented in 24 Rubens paintings. Serial art in modernist painting is unusually associated with a single technique. See, for example, Claude Monet's “Rouen Cathedral” series that presents a single place (the front of the church) in various lighting. The series covers 28 works that display the possibilities of impressionist art to display air and light. The serialism of serial art is not about themes or techniques but rather different structures between works.

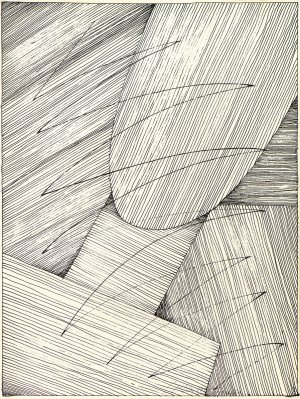

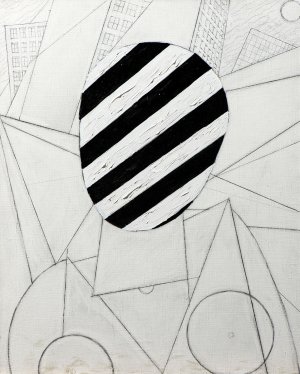

An internal structure is a value in itself. Yulikov’s minimalist works are connected by the artist’s denial of “staged compositions.” This is how Yulikov sees traditional structures that replicate the closed form of the world as a theatre. In his mature works, Yulikov nullifies everything he did during his experimentation period. Paintings cease to be narratives. “I make visual items”, notes Yulikov. “I can make texts. But that’s not what interests me”. The opposition of painting-as-item and painting-as-text is the focal point of Yulikov’s creative endeavors.

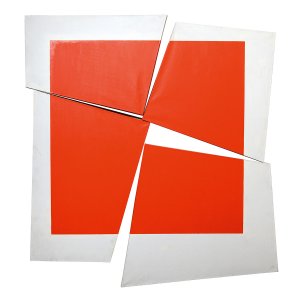

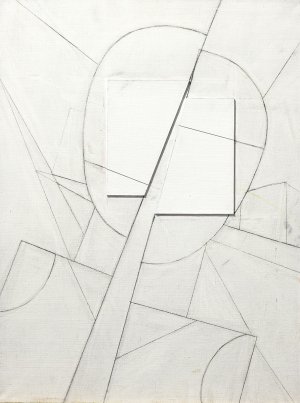

“Destroyed paintings” can be seen as a peak of the artist’s career. “Cubists destroy the image, but the world remains”, says Yulikov. “In my case, I destroy the world, but the image remains.” Yulikov did not produce a single complete manifesto of his theoretical views. However, the latter is evident from some of his statements. “The idea behind the painting composition is that you’re seeing a fragment but experiencing the whole.” In his “broken” works, Yulikov develops the difference between simulacrum and actuality, i.e. the difference between the way things appear to be and the way things are.

Paintings are both ideas and structures. Ideas refer to the world of the extrasensory, Plato’s cave. Structures reflect the understanding of a painting’s sculptural properties, meaning the material existence of an item. For the world of ideas, a painting is a plane; for the world of structures, a painting is an object that possesses surfaces, edges, hollow spots, and dense spots. Yulikov investigates the fracture between ideas and structures by breaking down the continuity of the painting plane. Structures are fragmented, while ideas remain whole.

Yulikov’s “Red Square” (dissolved) serves as a continuation of Kazimir Malevich’s “Red Square” (1915). The works of the two artists are frequently compared. Andrey Erofeev classifies Yulikov’s style as “postsuprematism.” However, this is apt only in the most general sense. In the same vein, all academic art after Raphael could be seen as the continuation of the “Raphael line.” All artistic challenges that are drawn in Yulikov and his structural considerations lie beyond the field of postsuprematism. In the strictest sense of the word, postsuprematism is the continuation of the “Malevich line” by his direct followers, including the Leningrad-based “Sterligov school” with its “cup-dome” method. Vladimir Sterligov (1904—1973), a former student of Malevich at the State Art Culture Institute, developed his teacher’s idea of the “additional element” in art, incorporating his very own additional element in the form of “cups/domes” to the elder master’s system. If we consider Yulikov as a postsuprematist, then the term itself loses all meaning. By the same virtue, all the post-war formalist generation could be named postsuprematist, even though they came from various art circles: Valery Yurlov (b. 1932), Leonid Borisov (1943—2013), and Mikhail Chernyshov (b. 1945), etc. The problem lies in the fact that they are more artists working in the abstract expressionism tradition rather than Russian avant-garde tradition.

Pollock was more available for public viewings than Malevich during the Thaw. The first big step towards new Russian abstract art came in the form of the 1959 American exhibition in Sokolniki. Works by Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, Arshile Gorky, and other artists could be viewed. At that time, pieces by Malevich were stored in vaults and were only accessible to a select few who could get into the museum workrooms. Hence the American exhibition was a key event for post-war Russian art. Russian abstractionism has a curious history: in the eyes of that generation, Malevich was more of a mythical figure than an actual artist.

The difference between the minimalism of Yulikov and the suprematism of Malevich lies in the time. Malevich lived in times of great change: the crisis of 1905, World War I, the Civil War, two revolutions, and the establishment of the USSR. The minimalism of Yulikov was born from the static world of late socialism which had few historic upheavals (such as Stalin’s death or the following Thaw) and the few disruptions that did happen were not as traumatic as the age of wars and revolutions. When viewed from the 21st century perspective, that period seemed to have completely halted all movement. This difference in lived time could not help but be replicated in art.

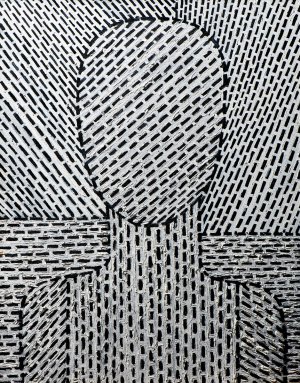

The static character of time is reflected in the space. Yulikov is a master of fine spatial transformations and discovering balances in formal fluctuations. Yulikov’s earliest works begin as a reduction of 2D forms to their basis. Even in his graduation illustrations for “Hamlet” (1969?), Yulikov already touches upon the head (of the title hero) as a structure literally cast behind a cell of dashes. This formalist approach to time results in a new sort of painting, i.e. creating structures through differently directed strokes. Yulikov will spend many years mastering the interactions and juxtaposition of painting elements.

Yulikov’s art is founded on graphic techniques. This is not a coincidence. “Being a book illustrator is a lawful and gainful employment”, notes the artist today, “everyone did books. It was a separate discipline. Typefaces are a discipline. All ‘formalists’ worked with books: Kabakov, Gorokhovsky, Yankilevsky, Pivovarov… Everyone treated me well. But I was unlike all of them.” In September 1968, whilst still a student, Alexander began interning at the Iskusstvo (Art) Publishing House. Afterwards, he will work regularly on publishing projects. Soon it was suggested that some of his pieces could be displayed at the Leipzig International Exhibition of Print Graphics. However, the works were not accepted. “It’s quality work but it does not go well with the Soviet exposition”, Dementy Shmarinov privately relayed to Yulikov10*. “This proved to be my cross to bear during my whole life”, recalls the artist, “Lyakhov11* told me: ‘Sasha, you’re like Robinson Crusoe.’ Emphasis on the last syllable.” Personal growth in the field of print graphics gradually brought the artist to understanding the limitations of the period and working beyond graphics.

American minimalism worked from revealing the language of 3D objects. American minimalism upholds the sculptural approach, while Soviet minimalism leans more toward a graphic approach. This is the source of their differences.

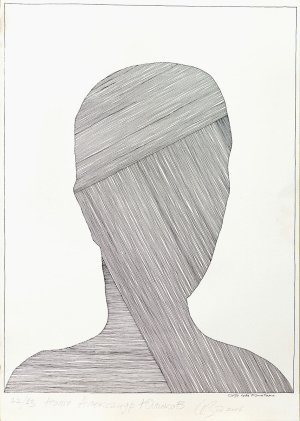

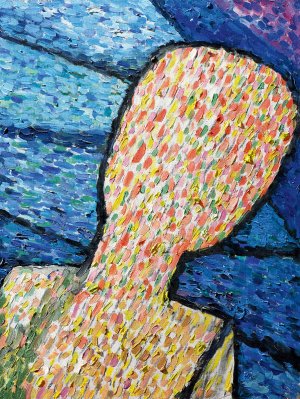

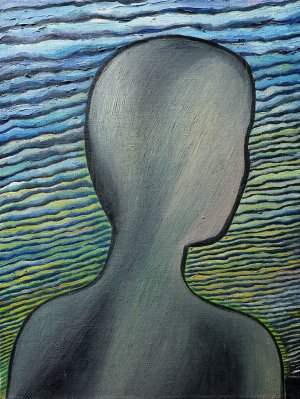

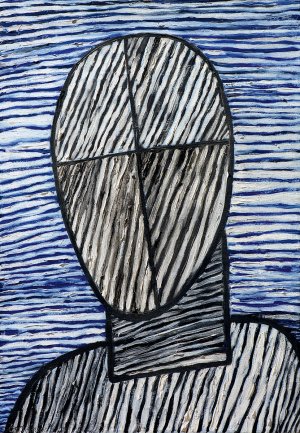

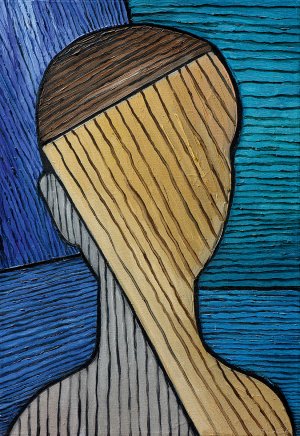

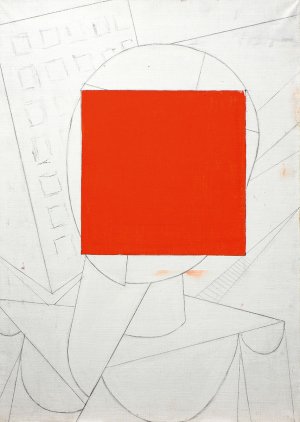

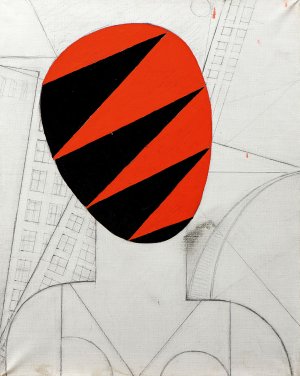

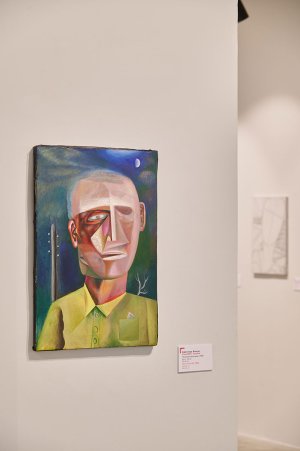

Print graphics allows for a greater level of abstraction than painting. The new 1980s “heads” by Yulikov originate in the graphic works created in Dzintari (Latvia). In his pieces from the 1980s and later, Yulikov combines minimalism with physically attractive images, meaning that the artist returned to experiencing paintings as their own worlds. Minimalism demands non-emotionality, lack of feeling, non-participation, and immateriality of the pieces. Yulikov’s minimalism sees a new, humanized form of abstraction with the head as a symbol of humanity.

Yulikov passes beyond the break between the abstract and the figurative. Neofigurativism is a trend towards overcoming the seemingly insurmountable border separating the two schools. Neofigurative artists see figures as symbols that reference the world of universalities (i.e. the world of ideas) rather than specific people or events. Unlike portraits, here figures are not personalized but are a combination of traits represented in the most general sense.

Anthropomorphism grants paintings more humanity. Images of people transport art to a whole different plane. Heads reappear in Yulikov’s art during the early 1980s, the darkest period of Soviet reactionist politics when many artists (including Yulikov’s friends) were squeezed out of the country, apparently forever. The dissident movement was completely destroyed. Metaphysics proved to be a pillar for many to lean on. The cultural significance of humanized abstractions is the convergence of intellectuals and the church it promotes. As early as with Kandinsky and Malevich we recognize that the latter’s cross and the former’s “mountain” and “horseman” are not just abstract forms but also religious iconography. Malevich and Kandinsky were interested in theosophy and anthroposophy, while Yulikov, Shvartsman, Umnov, and many other artists engaged in Orthodox Christianity as a mediating form of spirituality, not a stiff system of religious institutions but a humane support network for opposing the ideology forced from above. Befriending the priest Alexander Men was one of the most significant events in Yulikov’s life.

We should not overestimate the importance of interconnectedness and mutual influences in the artist’s work. Despite the long and close partnership with Mikhail Roginsky (who frequently lives in Yulikov’s studio when visiting Moscow from Paris), it proves to be quite difficult to uncover any influence Roginsky had on Yulikov (and vice versa).

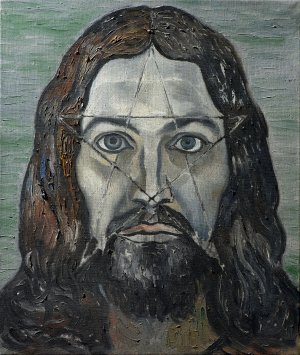

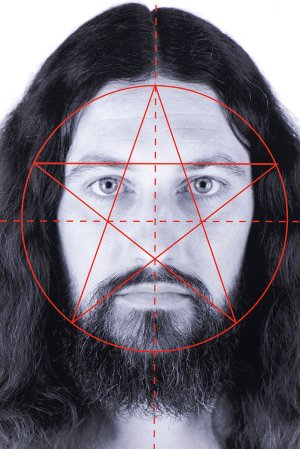

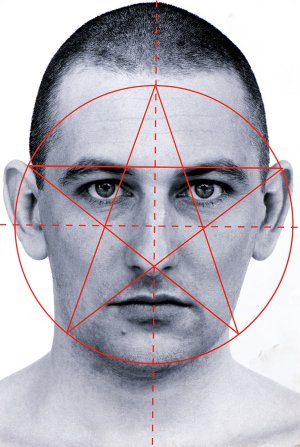

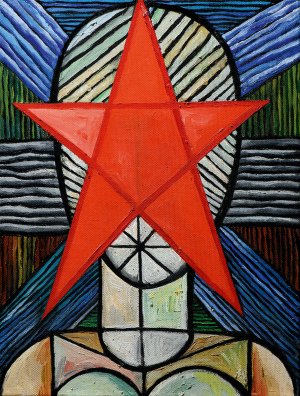

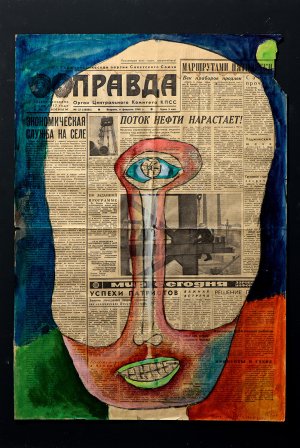

Similarly, despite his closeness to Sots Art circles and the 65-year friendship with Alexander Kosolapov, Yulikov has few works in that style (even indirectly). For example, “Cyclops Head” (1968) is painted unto the first page of the “Pravda” newspaper. But this is the limit of its Sots Art relevance. “Head with Star” (2004) seems to be primarily inspired by Leonardo da Vinci’s “Vitruvian Man.” The face is grafted onto the coordinates suggested by the pentagram.

Two photos of Yulikov’s performance art piece “Tonsure” (1976) are also displayed in pentagrams. “Tonsure” can be interpreted in a variety of ways. As a refusal of the Bohemian lifestyle which is associated with long disheveled hair. As an escape from “Christ makeup” (to quote a joke of Berlin Dadaists about Johannes Baader). But the piece can also be seen as a formal purification. The face returns to its original geometric parameters.

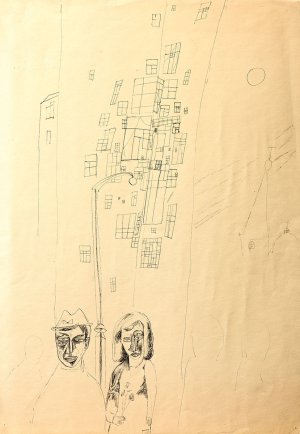

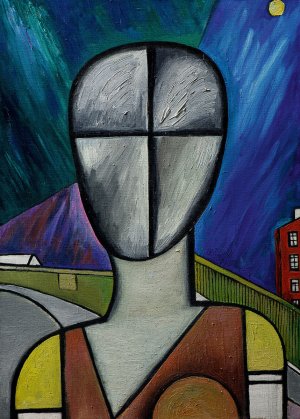

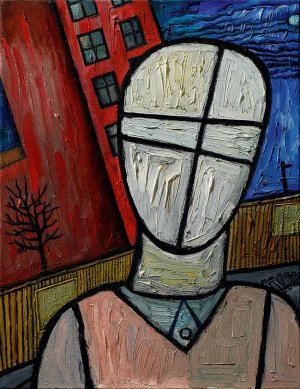

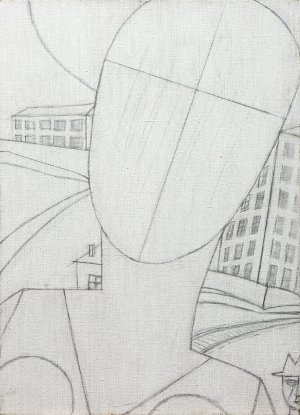

Yulikov is a Muscovite in every inch. He has spent practically all of his life on Gorky Street and in its vicinity. That’s why the “man and city” motive has been present in the artist’s work for over 60 years. The painting is treated as a window into the world. In this Yulikov doesn’t follow in the footsteps of Florentine Renaissance. Rather, the artist presents what can be seen from his apartment. We see the wall on the opposite side, full of windows each hiding its own universe. “Man and City” (2005) and “Man in the City” (2011) demonstrate heads on the background of multistory housing units with heavily emphasized windows. During the 2000s, Yulikov returns to themes from his preminimalist phase but treats them in a different light. The city is now more of a geometric space rather than a lived-in world. People are a part of a system of angles, figures, straight lines, and curved lines.

The head is also represented as an egg or, more precisely, an ovoid (a closed curve with a single symmetry axis). Individuality is gained by moving beyond the symmetry concerning the inclination angle, unstable elongation, differences between the two halves on both sides of the axis, etc. Even in this radically generalized style, the heads offer a limitless diversity of forms which the artist consistently varies, adding backgrounds that couple the heads in different ways. Various works, ranging from the “Self-Portrait” (1958) to the latest “unfinished” pieces, are united by the development of spatial systems. People are relegated to one of the possible forms of stressing the lines, thickening the space.

Yulikov’s “unfinished” works date back to the last ten years. They can be interpreted as “procedural art.” Most of the pieces are incomplete and, perhaps, will remain unfinished. That lack of coherence is a matter of principle. The omission of the final strokes relates to a specific experience of time. “Unfinishedness” represents openness to change that may happen in the future. Yulikov began the new series inspired by the “Unfinished” exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum (2016). For the first time in international museum praxis, the exhibition united around 200 works by various artists, ranging from Renaissance to contemporary art, with a single question in mind: when is an artwork truly complete?

During the late 1970s, Yulikov hosted an apartment painting performance piece that lasted several days. The piece showcased his life: each day was marked, depending on how it went, with a plus, a minus, or a zero. The painting continued the next day. There were still spaces to fill, even though the exhibition had passed. “The very process of painting shows that time continues,” notes Yulikov.

Notes

1* Les peintres futuristes italiens. Exposition du lundi 5 au samedi 24 février 1912. Paris, chez M. M. Bernheim-Jeune et Cie. Paris,

Imprimerie Moderne, 1912. 2*. The New American Realism. Worcester, MA: Worcester Art Museum, 1965.

3* Mel Bochner. Serial Art, Systems, Solipsism. In: Minimal art: a critical anthology / ed. by Gregory Battcock. Berkeley and LA: University of California Press, 1995. Pp. 92—102.

4* Lawrence Alloway. Systemic Painting. Ibid. Pp. 37—60.