Sergey Shutov’s solo exhibition “Qualia” at GUM-Red-Line Gallery includes 35 paintings created over the last five years. Most of the pieces were made specifically for the event.

Qualia is a philosophic term related to sensory-driven subjective emotional experiences. The sensations may be the same, but our perception tints them in vividly different colors. Sergey Shutov believes that art is connected with qualia and has spent over 40 years developing his own system of images.

«Qualia is any object that is inaccessible to all except the perceiver. This idea form the main instruments of the artist. The artist is not a user of the viewer’s mental conditions but a rare direct source of qualia. However, this is also a way of growing closer to the indescribable and inexpressible that belongs solely to the subject, the perceiver of an artwork. The artwork remains unthinkable yet also becomes imaginable, unspoken, and singularly possible.»

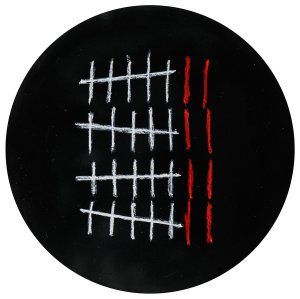

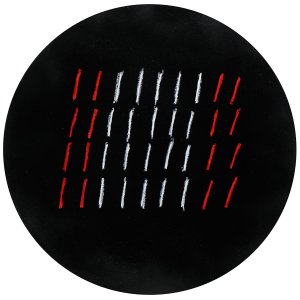

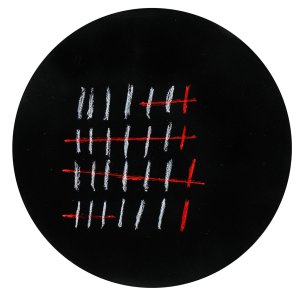

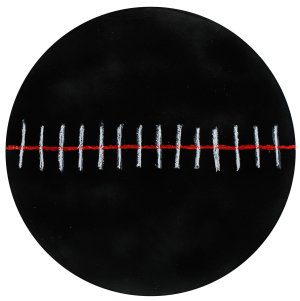

Shining is an important component of Shutov’s aesthetic. The artist works with light-reflecting materials. Shining is a material analog for the cosmic ether. However, such works as “Pepper” or “Eggplant” (both 2024) combine mysticism with buffoonery. On the other hand, the series “Time” (2024) sees the artist handling light-absorbing black paint over which white and red strokes and lines appear, counting down days, weeks, years, or even ages.

The exposition is a reflection on the “golden age” when the Moscow underground went mainstream. A small part of the gallery is covered with silvery polyvinyl chloride as a reference to Sergey Shutov’s late 1980s studio on Furmanny Pereulok. The showroom was completely encased in mirroring film. The screen offers a chance to view a selection of works by legendary “Ptyuch” club VJ Shutov.

Sergey Shutov (b. 1955) is a key figure of the Perestroika and democracy periods. Participant of “Pop Mechanics” concerts (since 1986), first member of Timur Novikov’s “New Academy” (1987), scenic designer on the film “Assa” (1987), curator of the “Assa” Art Rock Parade (1988), exhibitor at the first Sotheby’s auction in Russia (1988), president of the Art Technology Institute (1993), first Russian VJ (1994), member of the Russian Pavilion at the 49th Venice Biennale (2001). Starting from 1986, Sergey Shutov created over 50 solo exhibitions, including projects for the Tretyakov Gallery (2003) and MMоMA (2008–2009).

Exhibition curator ― Mikhail Sidlin.

HAPPINESS EXISTS

The Ethereal Myths of Sergey Shutov

Mikhail Sidlin

The essence of ether remains a mystery.

Konstantin Tsiolkovsky

It cannot be denied that quale exist.

Daniel Dennett

By what metric would Martian scientists recognize Earth art? How would they react upon learning that humanity has something of not direct usefulness and out of rational bounds but important in light of the so-called “feelings”, potentially even forming a transmitter of universal vibrations and bringing individual beings a certain kind of satisfaction?

Older aesthetics put too much emphasis on the matter of “taste,” a supposed capacity to distinguish between “beauty” and “ugliness.” Older psychology made far-reaching suppositions about a child’s cognitive functions from their propensity to value “beautiful” faces over “ugly” faces. Modern philosophy has already deconstructed this illusion of general beauty, leaving us with just one thing: qualia.

Qualia de facto stands in for matters of personal tastes. It’s something internally accessible and intuitively obvious yet thoroughly unobjective. A unique property of the sensory system directly relates to perception. Experience that is open to everyone but always different from person to person. It’s something that brings us satisfaction, be Paul Goerg Brut Absolu extra brut champagne or the colors of the Scrovegni Chapel in Padua. Or something that might be a nuisance. I personally gain no satisfaction from the finest Alsace Riesling. I find the wine bitter and whenever I taste it I am frustrated by my inability to join the throngs of wine experts. It’s a kind of annoyance and jealousy rolled into one. Each experience is represented by its very own qualia (quale in plural).

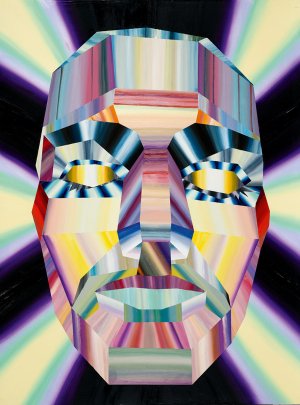

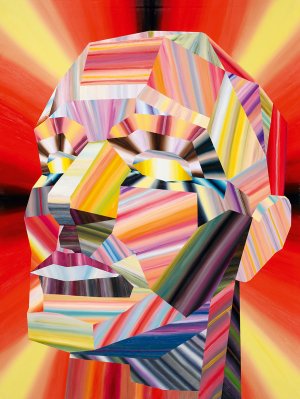

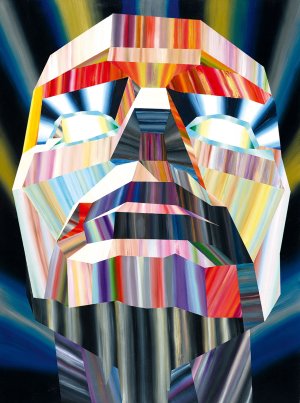

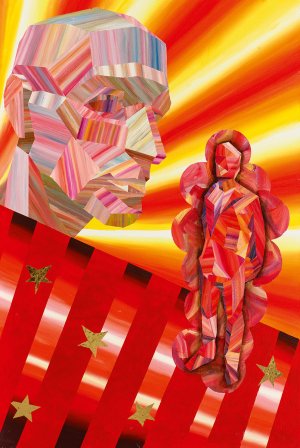

“Three Profiles (a)” (2023) by Sergey Shutov is painted over a shiny background covered in spots. The effect is obvious. But does it amaze and charm? Or aggravate and hypnotize? Or, perhaps, all of the above? The immediate individual reaction of the neural system to this irritant is qualia. Qualia can be objectivized: for example, we can write down that the positive reception of these spots reveals a choleric temperament, while a negative perception bespeaks a phlegmatic temperament. However, these observations in no way enhance the temperament theory by Hippocrates and Galenus. Most importantly, we gain no insight into Shutov’s art, the general notion of his works being conducive to proactive readings notwithstanding. Such pieces can be termed to be “qualia-oriented.” This is possibly what unites them. The paintings are frequently based on simple compositions, reflective of classical canons. “Three Profiles (a)” and “Three Profiles (b)” follow the Ancient Greek technique of isocephaly: the heads are placed on a single level. The faces, however, are formed out of planes (mostly triangles) painted by multi-directed strokes, similar to modernist architecture and not really recognizable as human. Architectonics are at the forefront. Classical images are but remote reference points.

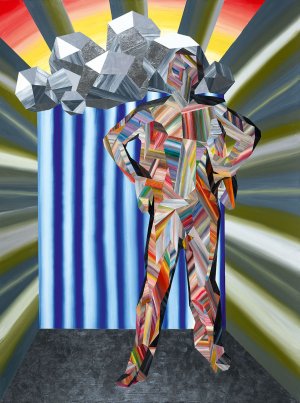

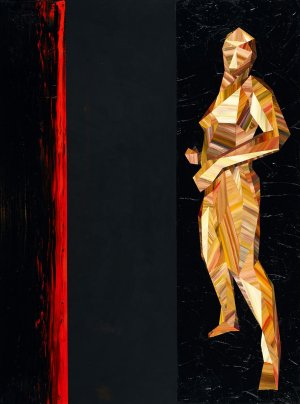

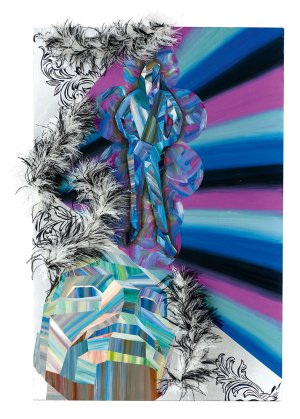

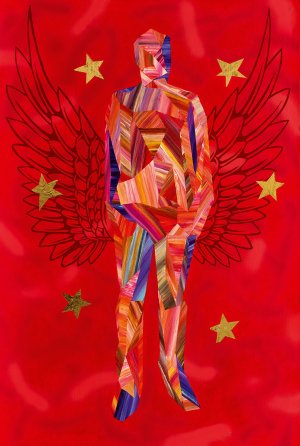

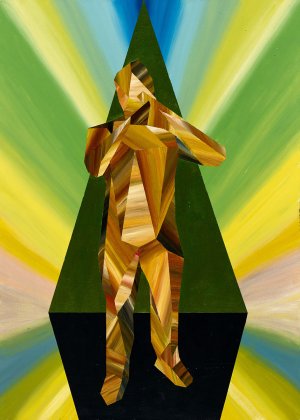

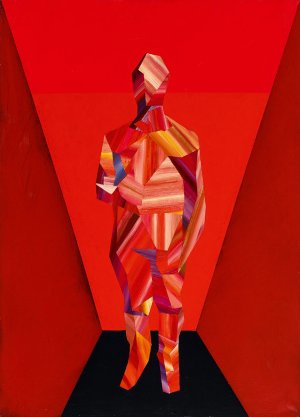

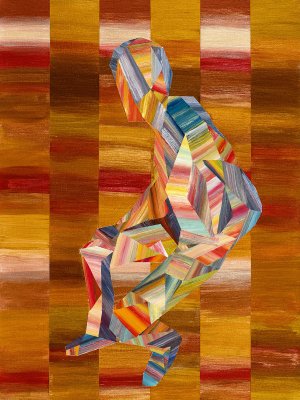

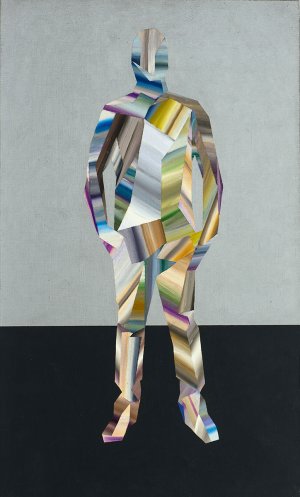

In terms of technique, traditional painting focuses on uniting the figure and the background, drawing together the various dimensions into a single piece. Shutov goes about resolving this task by boldly disregarding traditions. His figures are frequently removed from the backgrounds, even set against them in material, technique, color, and texture. The “Other People” series is a good example (2022, 70 × 100 cm). At the same time, figures are still connected to the backgrounds by the shine, radiance, and irradiation of the backgrounds.

Shutov’s figures are often weightier than the backgrounds. This is achieved through a variety of methods, both purely painterly and with the use of unorthodox materials. That’s what produces the unique “Shutov effect.” And the immediate recognition: “That’s a Shutov!” His figures float in the space. The light coming out of the center of the composition seemingly holds the heads of the figures upright. See the painting “Untitled (Head 1)” (2020). This light is similar to the halos in sacred icons.

The space of Shutov’s paintings isn’t empty, it’s a living, pulsating creature-substance, sometimes flattened and radiant, sometimes rough and bumpy, full of wormy lines and streams of color. “There’s matter wherever there’s space. The space itself is substantial. One is unthinkable without the other,” wrote Konstantin Tsiolkovsky1. He was a proponent of the ether theory and thought of interstellar space as not devoid of content but full of a special substance that produces stars and subsumes the latter at the end of their cycles. Sergey Shutov promotes the ether theory through painting. The space of his paintings is matter.

The heroes of Shutov’s works live in the space described by Tsiolkovsky. That space is not subject to the laws of gravity or friction. The figures float rather than stand. This locus is penetrated by unseeable beams or waves. Shutov masterfully makes these energies apparent to the viewer. If the autogenic theory is to be believed (shared not only by Tsiolkovsky but also by biochemist Alexander Oparin), then the indivisible materiality of space serves as a solid foundation for moving from dead to living matter. Moreover, one type of matter is mostly similar to any other (Tsiolkovsky noted that crystals are examples of “life” in “artifice”2).

The exhibition symbolizes the Universe. The ideally white modernist cube corresponds to the contemporary theory of interstellar voids which house only celestial objects (i.e., artworks). The ether theory postulates that space cannot be empty. It’s always full, at times with the most unusual forms of beings. Tsiolkovsky proposed that someday we will find beings nurtured by solar energy3.

“I need a miracle, it's more than physical,” sang Coco Star to the accompaniment of Fragma in the early 2000s. A hit of the international trans scene. It’s relevant to remark that Sergey Shutov is the sole Russian who was able to create visual art fully in line with rave culture. And not only as the first Russian VJ and constant guest of the Ptyuch Club during the 1990s. But also as a painter.

Rave relates to a boundless feeling of our joint remoteness. Total submersion into the rhythm, lack of spatial coordinates, mass co-being, shortage of intimate contact. Those are the features of techno parties. Shutov’s art is for people who prefer to live at 120–150 BMP but are open to slow dissonant harmonies. Perhaps, it’s appropriate to discuss art in musical terms. Thus, the figures from the “Other People” cycle can be “heard” as highly repetitive mainstream house, while the “Time” series appears as dark ambient: radio interferences, groans of remote galaxies, operatic singing, forceful sounds that combine to create impenetrable noise over a steady rhythmical pattern.

Sergey Shutov is an artist of the alternative mass culture. House is alt disco. Techno is alt synthpop. Et cetera. A key feature of the underground is opposition to popular tastes, resulting in the opposers becoming popular themselves. DJ Groove, the author of “Happiness Exists,” the evergreen hit of late 90s Russian club culture, was a star of the alternative wave. Shutov was lucky: painting does not require the artist to be loved to death.

One of the Moscow hippies, Sergey Shutov started to make art in the 70s. Most of his few works from that time have not been preserved. Hence why his career had its proper beginning in the early 80s. By that time Shutov was already recognized as a guru of the underground. The 1982 “Canon” (written with Arkady Slavorosov) opens the “Anthology of Russian Rock Samizdat”4 and is very much a founding text. It was circulated via typing machine-produced leaflets and in home-made almanacs. Shutov already had the experience working as an assembler and a freight handler, as a zoo keeper, and a Planetarium lecturer. Shutov is the canonic hero of “the generation of janitors and watchmen.” Participation in Gruzinskaya Street exhibitions ensured that he was formally seen as an artist (only 40 years after being accepted by the City Committee of Graphic Artists Shutov obtained a studio from the Creative Union of Russian Artists, the Committee’s successor).

“Canon” envisions that everything in Russia could be seen as a prophecy. Even the Russian word for “prophet,” i.e. “пророк,” could be read as “проРОК,” i.e., “about Rock,” a signifier of the coming of rock and roll. Philosophy, bias, alogism, humor. Individualized language, emotional orthography, self-styled myths. For over 50 years, all of these traits were the building blocks of Sergey Shutov’s creative process. Shutov was one of the protagonists when art became everyday life and everyday life became art. The late 80s and early 90s were a time of endless carnivals. The exposition reminds viewers of the “golden age” when Moscow’s underground art turned into mainstream. A small part of the gallery is covered with silvery polyvinyl chloride as a reference to Sergey Shutov’s late 1980s studio on Furmanny Pereulok. The showroom was completely encased in mirroring film.

Post-Soviet art is connected with Soviet aesthetics in the same manner a mushroom is connected with a rotten tree stump. In comparison with Sots art which lives off Soviet posters or Moscow conceptualism which, similar to a sort of black grime, grew out of children’s books, Shutov springs out of the unforgettable Soviet youth magazines, including “Explorer” and “Engineering for Youth.” That basic root link with Soviet fantastic graphics does not, however, result in a lot of similarities. Shutov never copied magazine illustrations in format, technique, or composition. Just compare him with Dmitry Gutov.

Conceptualism views art as a language. Shutov followed another path: he filtered Russian cosmism through hallucinatory realism. Works such as the “Scientist” (2006) are clearly influenced by Soviet science fiction illustrations. But the portrait, displaying the scientist with a beaker at hand, radiates with bold colourful lines which place science firmly within the realm of rave. Technologies via techno.

Soviet fantastic graphics are still unrecognized as a distinctive phenomenon. It could have served as a springboard for understanding the artworks of Sergey Shutov. All these images of cosmic spaces, future cities, Saturn’s rings, and Martian voyages partially illustrated actual scientific discoveries. But mostly they were pure artistic fancy, inspired by Russian and Western art of the first half of the 20th century. The line from nonconformism to science-adjacent illustrations is evident. For example, Victor Umnov (1931– 2022) worked as an illustrator with Yeremey Parnov5, while Vladimir Nemukhin (1925–2016) served as “artistic designer” at the “Explorer” magazine6 .

Adventures/science fiction formed an alternative mass culture in the Soviet Union. In contrast to the ever-prominent official art, artists and filmmakers created their own worlds where ideologic issues would appear only as afterthoughts, completely secondary to engaging storylines and tantalizing descriptions. “Planeta Bur” (1961) and “Amphibian Man” (1961) vs. “Virgin Soil Upturned” (1960–1961). It’s obvious how Shutov engages with the heritage of Soviet “pulp fiction.” However, that connection goes even deeper.

Shutov’s art originates from Soviet cosmism but is distinct from it. It’s Soviet cosmism through the prism of rave culture. The forefather of Detroit techno also watched the stars via the lens of cheap magazines and B movies. But can an exhibition hope to replicate “the endlessly expansive cosmic ether, the guide of light” (Tsiolkovsky)7?

The sky observable from the cosmos seems fully black. That’s because the blue color is a feature of Earth’s atmosphere. As soon as air is removed, it’s revealed that humanity is surrounded by the limitless pure blackness of space, disturbed only by bright spots: the stars. During the night, these balls of light appear to be slightly red when viewed from Earth’s surface. The reason is the same: the thick gas dome held in place by gravity. This constant environment primarily refracts beams with the shortest wavelength, i.e., purple beams. Beams of a reddish hue are refracted to a much lesser degree.

Canvases from the “Time” series (2024) were painted over with light-absorbing paint that is used in movie theatres to provide a comfortable viewing experience. The backgrounds appear similar to cosmic spaces. Lines transform limitless spatial rapture into calculations of time. The starry sky above becomes beholden to the laws of numbers. The connection is direct and immediate: in the ancient city of Nippur time was calculated by noting the movement of the sun against the sky. The Sumerians divided each year into twelve months and counted each day as twelve hours. We still follow the Sumerians in this respect. The more we dive into the blackness of night, the more we desire to count up our progress. Ancient people counted up days, weeks, and months by making notches. This form of calculation seems to precede the advent of civilizations and is still prominent in places without clocks and phones. Robinson Crusoe stuck a stick into the sand and made notches on it every day. Prisoners still make vertical and horizontal notches on walls. Sergey Shutov uses this archaic way of calculations and experiments with it by adapting the notion into a series of abstract paintings about the passage of time.

“How vast and free is the space around Earth, how full of light and empty it is. What a pity!… How we herd ourselves upon the Earth and how much value we place on each spot under the sun for growing plants, building housing, and living in peace and quiet. When I ventured forth into the void around the rocket, I was amazed most of all by that vastness, that freedom and ease of movement, that mass of senselessly lost solar energy… What precludes mankind from constructing greenhouses and palaces here and living without strife?…” That’s what Konstantin Tsiolkovsky mused through one of the characters of the fantastic story “Away from Earth”8. Shutov art brings us into the future of mankind when the old Earth will appear as a prison which for a long time didn’t allow mankind to freely float in the ether and fly to countless stars.

“Maybe, humanity will change,” said Franklin. “To no longer require spacesuits or houses in the void.” “And, maybe, even earlier,” added the Russian, “we’ll create a gas atmosphere in the ether and put it to use!”9

References

1 Konstantin Tsiolkovsky. Loving Oneself or True Selflove. Kaluga: Author Published, 1928. P. 17.

2 Konstantin Tsiolkovsky. The Origin of Life on Earth. Can Life Be Transferred from Other Planets to Earth? // Nature’s Workshop. 1922. #1. P. 13–14.

3 Konstantin Tsiolkovsky. Living Creatures in the Cosmos // Konstantin Tsiolkovsky. Dreams of Earth and Sky. Tula: Priokskoye Publishing, 1986. P. 271–272.

4 Golden Underground. Full Illustrated Encyclopedia of Rock Samizdat. 1967–1994. Nizhny Novgorod: Dekom, 1994. P. 200–201.

5 Mikhail Yemtsev, Yeremey Parnov. Over the Green Strait // Explorer. 1962. #1 (7). P. 45, 56, 61.

6 Explorer. 1962. № 1 (7). P. 160.

7 Konstantin Tsiolkovsky. Changes in Relative Gravity on Earth // Konstantin Tsiolkovsky. Dreams of Earth and Sky. Tula: Priokskoye Publishing, 1986. P. 41.

8 Konstantin Tsiolkovsky. Away from Earth // Ibid. P. 115.

9 Same. Ibid. P. 124.

Artist:

Sergey Shutov