Abstract thinking, abstract art are readily recognizable terms. But few understand how they came to be the basis of revolutionary artistic processes in the early 20th century.

Artist Alexandre Beridze and many art historians believe that art chronicles humanity’s existence on earth and that this sort of chronological approach enables museum workers and art specialists to create collections fully in line with the development and evolution of people. A graduate of the Tbilisi Fine Art Academy, Beridze has lived and worked in France for 25 years. Since 2005 he creates abstract art. In spite of his fondness for photography, video, literature, and philosophy, Beridze sees abstract art as the primary medium for expressing his unique internal world and presenting his very own understanding of the Universe. This is something to bear in mind when viewing Beridze’s paintings.

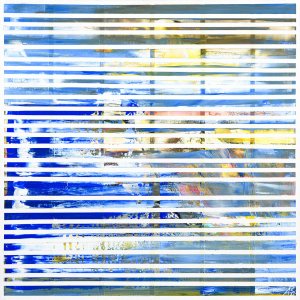

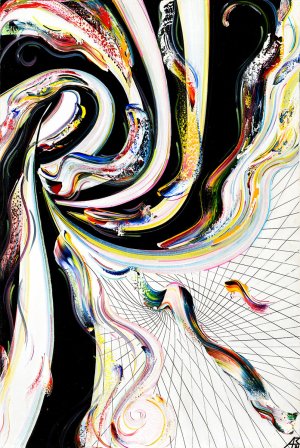

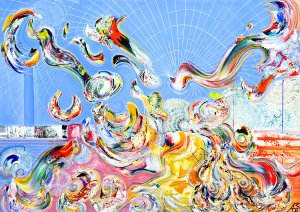

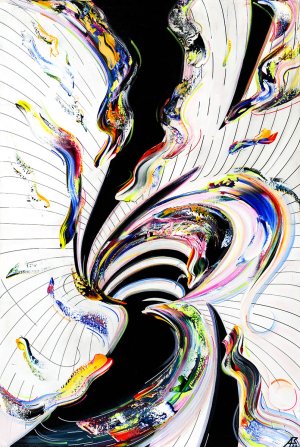

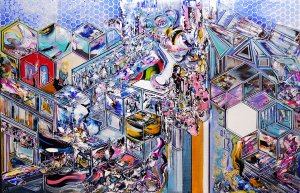

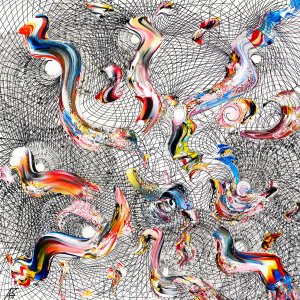

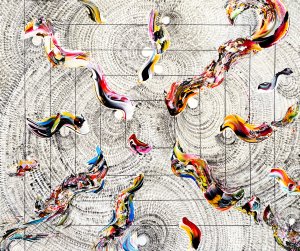

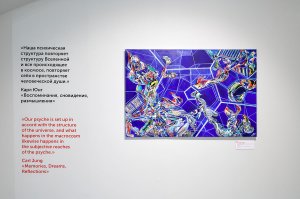

The GUM-Red-Line Gallery includes new works from the “Transpsychology” series that were created in the artist’s French workshop as well as pieces from the “Reflection” series that brought the artist renown in both artistic and, perhaps most significantly, scientific communities thanks to his collaboration with the mentalist Jean-Louis Tripon. Their joint book “Discovering Our Mental Life” (À la découverte de notre vie mentale, Les Editions Sydney Laurent, 2018) is an experimental investigation into art as a visualization of the thought process. Tripon referred to the relevant works as “mental figurations” that beautifully showcase the thinking patterns, something that is never possible with verbal forms, in a variety of color associations.

Beridze’s works are also beloved by scientists around the world. Most notably, a team of Columbia University discovered numerous confirmations that his pieces provoke reactions in people with autism or Asperger’s syndrome who are well-known to be irresponsive to visual images; the Paris Brain Institute and Europe’s largest children’s autism ward at the Pitié-Salpêtrière Hospital study how Beridze visualizes thought.

Beridze frequently participates in scientific conferences and wrote many publications on the links between science and art.

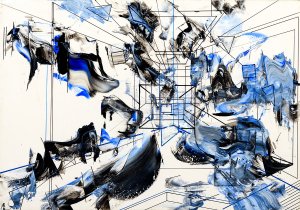

The “Abstract Thinking” exhibition highlights combinations of Beridze’s paintings, graphic works, and photographs that are presented to the public for the first time ever. Guests will be able to trace the connections between the artist’s painted worlds and photographic experiments, all of which impart a structure-focused and energy-charged way of thinking. Varied colors, bold graphic and paintings spaces, constant search for new forms ― all this makes Beridze a cultural phenomenon that both brings joy and evokes deep reflection on the nature of art.

Discovering worlds

Meeting with Alexandre Beridze is sure to be an important event for any person. He is a striking but sincere person, a lively and fascinating talker yet also a possessor of an incredibly structured mind that seems to be made to overcome his chaotic creative side. In conversation with curator Marina Fedorovskaya the artist uncovers the secrets behind his personal growth and his ruminations on art.

What were the earliest and most vivid childhood impressions that became a solid part of your world?

I’m surprised that people can recall their childhoods in detail. I do recall some of my own childhood, but these are not emotional moments but just some chronologically arranged stories. My mom told me many things, but one of my earliest own memories (and one of the most distinct) has to do with my own hands with bloodied fingers. My grandfather, also an artist, was teaching me how to draw. As all boys, I loved planes, tanks, soldiers. And always asked my grandpa to draw me a ship, a plane, something “about war.” My grandad experiences the war firsthand. And he didn’t like the war because he actually fought it. But he did draw it all but joylessly. One day gramps had a bright idea. I was five. “Sasha, let me show you how to draw. That way you can draw tanks, planes, whole armies by yourself.” I liked the idea. “Yes, grandad, let’s try.” Grandad gave me a set of pencils and a very precarious Neva razor and explained that professionals never sharpen pencils with a sharpener. Pencils are sharpened to do specific things: drawing, linework, painting on surfaces, etc. At that time, we had limited options, so each pencil could be sharpened to do anything. So, grandpa spent three weeks teaching me how to sharpen pencils. I often cut myself and that’s why my fingers were bloodied. But I did learn, both to sharpen pencils and draw. I still have a photo of me as a kid, sitting and drawing on a bench. I had received a set of German marker pens. All the boys went to the courtyard with toy cars or trains, while I brought my pens.

I do try as hard as I can to preserve the name of my grandfather for history: Fedor Kholenov. His real surname was Kononov but he had to change it after the revolution. He was a fairly significant artist, by the end of his life he had a studio in Lviv. He decorated all the bus stops between Lviv and Poltava with mosaics. Thanks to grandad I always painted, from my earliest years. And that had an impact on my life.

In 1991 I enrolled in the Tbilisi Fine Art Academy and decided to study graphic design to later get a job in advertising or something like that. That was a popular vocation. So I studied at the Graphic Design Faculty, not the Painting Faculty. Moreover, my family was livid about the very thought of me becoming an artist, moreover enrolling in the Academy. I’m the only son, and my dad, a businessman, couldn’t imagine a situation when his heir wouldn’t continue the family trade. My dad didn’t like my grandad. But it just so happened that grandad had a greater influence on me growing up. When I begin considering in detail my childhood, from my birth all the way to the age of 10, I understand that my granddad introduced me to Russian culture. He read Pushkin, Saltykov-Shchedrin, Lermontov. The same Lermontov who went to Pyatigorsk and died in a duel… But most importantly, and I'm especially grateful to my grandfather for that, he instilled a love of classical music within me. I first listened to it because it had a nice sound. My grandad had two favorite composers: Rachmaninov or the silence. He loved the Piano Concertos No. 2 and 3. Every Sunday after lunch we would sit down and listen to music. Gramps took me to Mariinsky and Bolshoi Theaters. Naturally, I didn’t like all that at the time, but over the years I understood that grandad helped me discover culture in general. However, in my father’s lifetime I had to constantly struggle for the right to do art.

Your family moved at some time from Leningrad to Tbilisi. Before that you have moved to Leningrad. Later, you lived in Moscow and then moved to France. I think that all these moves helped you in getting used to new places. Is that so?

No, it was never easy. We moved to Tbilisi in 1986, exchanging a five-room apartment in the center of Petersburg for a five-room apartment in the center of Tbilisi. We even had to pay extra. Three or four months after that the privatization law was passed, so we had to sell, not exchange apartments. I remember that because it happened on August 16, and in fourteen days I went to school where I felt the difference between Russia and Georgia on my skin. It was hard, I was coming back home in tears… Even though one of the reasons why we moved from Petersburg was the constant “Georgian” taunts. I was always a good student, but in primary school our class was headed by a teacher with a Georgian surname. During PTCs people would practically tell my mother that Georgians always stick together, and that’s why I got good marks. Yet my mother is a Russian, even though she did take my father’s surname. Now she’s Ludmila Fedorovna Beridze. But at school all I heard was “Georgian-Georgian-Georgian.” And what do you think I heard when we moved to Georgia? The first thing I heard in Georgia was that I was a Russian because I couldn’t speak Georgian. That shocked me.

Yes, welcomed by strangers, shunned by those closest to you. It’s the same story for all people with mixed origins…

Now, of course, I can speak Georgian but I do have an accent, so Georgians immediately realize that it’s a learned language for me. As is the case with French.

But, other than the language, everything else was also different: the culture, behavior, everything. Daily life in Tbilisi diverged significantly from that in Russia. As an example, you had to immediately get to know all your neighbors. And we came from Petersburg where we didn’t know even half of our neighbors. In Tbilisi people formed true communities. Thankfully, Tbilisi is a multinational city, so I quickly learned the ropes.

Speaking about Georgia in general, I matured there as a person. Georgia gave me an understanding of life and interactions between people. If you wake me up in the middle of the night and ask me who I am, I will most certainly say that I’m Georgian. When I went back to Petersburg and met up with my former classmates, I saw them just as kids. Georgia gave me, and not without a fight and a broken nose, a place under the sun, in school, in our neighborhood, etc. I understood that you have to fight for your place in the world, in the pack. And learn to make a choice.

It's curious that the move from Leningrad to Tbilisi and later to Paris, not even Moscow, proved to be so crucial for you.

Paris also changed many things. But the most important thing I realized would become the theme of the Venice Biennale: “Foreigners Everywhere.” The theme is almost about myself… But truly major changes began happening in my life at the end of 1998 when I decided to go abroad. In 2000 I almost accidentally went to France thinking that it would be a short trip. But that short trip is already going on for 24 years, half of my life. And I still encounter tremendous differences and inconsistencies between the French, Russian and Georgian ways of thinking but I am able to maneuver between these identities.

Could you speak a bit about your favorite studio which, if I’m correct, is located on the Atlantic?

It just so happened that I divorced my wife and went for a visit with friends to the Atlantic. Just for a brief time, to weather out the storm and give in to my hobbies of painting and drawing which I wasn’t able to give my time due to various reasons. 18 years passed and I still live on the Atlantic. I’ve understood that it’s very beneficial, geographically, ecologically, aesthetically. It’s very beautiful here, near the ocean, and my whole internal world changed. Most of the time I spend in Paris, but I mostly paint in my studio on the Atlantic.

It seems to me that the Atlantic nourishes you visually as an artist. Even though nowadays artists are mostly focused on the inside rather than on the outer world, the external is still of paramount importance.

Certainly! But when I was at school, without a complete wish of becoming an artist, I still was really good at drawing, I won competitions and so on… I loved geometry and easily handled spaces. I can readily imagine and present a voluminous figure. I saw the world through a system of coordinates. This was always a part of me, just like my fancy for math and putting things in order.

Even at my place, everything is arranged very neatly. Some say that it’s a symptom of Asperger syndrome. I don’t know if that has anything to do with it, but autistic people react in surprising ways to my paintings. Columbia University researchers confirmed as much in our joint project. At Sorbonne, I’m going to write a dissertation on the connection between art and autism spectrum disorders. In Moscow, I’m also researching art therapy and art psychology with my colleagues at the Moscow City Pedagogical University. I initially wasn’t all too serious about all this, but with time I’ve understood that this field fosters much development. Psychologist Svetlana Pokrovskaya made me realize that.

So, in essence, you base your works on an internal metaphysical understanding of the world and the psychology of perception?

For me, the whole world is based around geometry. Everything from Pythagoras to Goethe, speaks to this. Goethe said somewhere that many beautiful things inhabit the world in a divided form and the goal of our spirit is to find the connections and thereby create art. Thanks to Goethe and many other philosophers we understand that a talented artist shows us how they experience the world, what their world is about. An artist in a way brings the world inside himself and creates a sort of a universum. The artist exists in parallel with the surrounding world and is brought together with it through artworks that are created by virtue of the artist’s vision.

Yes, I most certainly see internal worlds in your works, and these worlds are numerous, sometimes they almost don’t fit into a single work but require development, monumentality… How did you recognize that you wanted to do art?

This is something that I always felt. Perhaps, this is going to sound a bit boisterous, but I knew from childhood that I had a certain mission in life. I just didn’t know how it would reveal itself. I thought it would be through sports and I seriously trained. But as I grew older, I started to realize that it would have to be through art. My grandfather had an amazing library with many books on art. And one of these was a German publication dating back to 1876: over 800 Rubens lithographs. It was a thick volume with a beautiful red cover. It turned out to be the sole book of my coming-of-age, you know? That book had a profound, almost erotic impact on me. That Rubens album with the ample-breasted women… It seems weird, but even my sexual awakening occurred in a sense through art.

Your abstract pieces sometimes reveal an almost Rubenesque excessiveness, passion, and vitality. Incidentally, after visiting German museums specifically, I realized that Rubens tends to be undervalued in our times of postmodernism and metamodernism.

Tremendously undervalued! It’s also important that lithographs are black and white, so there is a contrast of form, a density of composition. Rubens has practically no white spaces. This is very interesting indeed. To take another example, Bruegel has much more nature, landscapes while Rubens is all about density and saturation. I couldn’t even distinguish a human figure from a tree branch. Everything is beautifully intertwined and crisscrossed in Rubens.

Could you briefly explain how you see the most important art trends of the 20th century that you’re in dialogue through your art?

Yes, this is an important question, I think that everything in the world develops in a spiral. In cycles. We have a saying: return to where it all started. But we don’t really return to a starting point, we’re always a level above it. That way the spiral forms. The Universe spirals away, even Earth flies in such a pattern. Water goes down the drain in a similar way. This reveals that cyclicity. Abstract art was created over a hundred years ago, it made a splash, it had a resonance. And I think that in that century we made a circle around ourselves and returned to the starting point, but a level above it thanks to the experience we’ve gained over the last one hundred years. A lot happened in that one hundred years: art shifted from the classics towards full-on negation. That’s why in my “Manifest” I, in some way, lay blame on Marcel Duchamp who was one of the enforcers of removing painting from its central position in art.

At the Academy, we’ve had a wonderful teacher: Konstantin Chkheidze. He explained to use the theory of four mass cultures and painting which establishes the mainline. And even changes in art styles still happen through painting. Even Duchamp grew to understand (and admitted) that painting would return to its leading position in about a century.

That’s why I see all the changing styles and paradigms of the 20th century as a normal process of development. We alter some things but ultimately return to a point when we have to construct a new reality, a new direction. And I believe that the only thing that provides us with the necessary footing is the history of the best works of art, those same works of art that provided footing for all the previous generations of artists.

Definitive beauty standards that each of us is given upon birth are important to me. It’s no wonder that we see the surrounding world as an ideal.

I think your art is more so about the beauty of internally understanding your world, the beauty of discovering yourself…

My sculpture of a man in a globe is about learning about oneself. My key message is that we’re all parts of one big world but we also hold that world in ourselves. And I feel that it’s necessary for artists to show other people through their art how the world is constructed. Because art is a way of experiencing your connection to the Universe.

The ancient sources of art and culture originally were cosmologic in nature. For me, art is a symbolic way of imparting the highest truths. Art existed long before science and initially housed science. For thousands of years, art was one of the driving forces for the development of civilization. But at a certain point people broke it all down, so now we have science, philosophy, and art as separate entities. As I understand it, we have a sort of big cloud of all truths, knowledge, and interpretations. And certain people are able to connect to that cloud of understanding the world. For many mathematicians, starting from Pythagoras, a key question is whether math always existed by itself or whether it was created by humanity? And Pythagoras thought that math always existed.

Personally, I think that there are some nuggets of knowledge which only some people can access. But everything exists in unity. That’s why the link between science and art is important for me.

And when we’re talking about abstract art one of the best references is music. There’s nothing more abstract than music. And there are a lot of focal points that music and math share. Here we have to return to Pythagoras and the basic seven tones. These are all the mathematical foundations of the principal truths of our world.

And though perhaps this is somewhat pretentious but I really do want to present and trace that line that brings everything together through my work, my art. Nothing is scattered; everything is united in the general structure of the world. Our goal is to find that general structure and not to chase separate phenomena. Humanity’s trouble is that starting somewhere from the middle of the 20th century we’re going too deeply into each sphere. And when you go deep you lose the big picture. But interaction is just as important as deepening.

Yes, intersectionality. And we can even say the dissolution of distinctions between genres has been a hallmark of art for a long time. Scientists are increasingly collaborating with artists.

Tell me how you work on your series. The exhibition will focus on two series: “Transpsychology” and “Reflection.” I think that each series is a certain stage, maybe even a chapter in a complete story that you just have to keep on writing till you’re done. Am I right?

Everything comes from my initial concept. I don’t give my paintings titles, but I do title series. And even if I want to, hypothetically. do something different that will go beyond my series I usually can’t do it. In a way, I’m not responsible for creating a painting. I frequently paint at night and when I wake up, I sometimes don’t understand what exactly I painted, how I painted that and what I thought about as I was doing it. I don’t even smoke while I paint because I can’t remove myself from the painting process. Only later, retrospectively do I realize that something moved me. I never visualize a painting that I’m working on, there is no image that I’m trying to capture. So, in spite of my wishes, I can’t leave a series before its completion. It’s something of a unified statement.

So, you’re inside of it, this world, as a sort of an elemental power?

Yes. There are certain paintings that I think of as transitional. But if you look at them together, you’ll understand when and why they were made. Paintings form for me a unified guiding line. Within each series, I have a specific manner, each series is recognizable as such, and that’s what critics often look out for. But in each series that recognizability is different. About ten years ago, I was critiqued for lacking my own signature manner. Nowadays, this cannot be said because if you view art as a progression then you will see specific traits of a style which change from one series to another. And as a highly efficient artist I can’t stay within one series for too long, I move forward never knowing what awaits me there.

There’s currently much interest and even a trend for abstraction, but fashions are quick to fade. In reality, abstract art is deep and subtle. I’d suggest it turns to very profound physic matter. And I do think that when a person begins doing abstract art, it’s a very serious, even momentous occasion…

Yes, very serious, I agree. You don’t know what you’ll encounter, what will be the result, and yes, it can be a provocative measure, you’re so right about that. I was in a way fortunate enough not to paint for a prolonged period. I did paint in my head, and that was the time when I moved from figurative to abstract painting. I worked a lot with graphic design, did corporate identity projects, and my work was always somehow connected with geometry, graphic art, so the move towards abstraction was a logical one for me.

I had a rather conscious switch to abstract art. The problem with abstract art is its seeming simplicity. In the last 10–15 years a lot of new artists who never even knew how to draw began working immediately with abstract art, as it seems to be accessible. I chose abstract art not because of its simplicity, quite the opposite, it was a conscious decision that I made as a person who already accomplished much both in art and design, and not because it was all easy or cool… I’m still reminded of that awful film “1+1” (“Untouchables”) where the main hero sprays a whole can of paint onto a canvas and says: “It’ll sell for thirty thousand!” Instagram is full of people who empty paint cans in a similar manner…

This devaluation does put real artists constantly between the hammer and the anvil… Because it’s difficult to present yourself and your own views on painting.

Yes, and art is one of the ways of learning about the world and yourself in this world. The sculptures that I do in Paris speak to the same thing, about looking for your place in the world. But to find your place in the world you first need to know how the world works.

Is photography your own way of “reading” the surrounding reality and its signs? I thing that it’s one of the ways of decoding our surroundings. It’s not about capturing documentary, realistic shots (in the Barbizon School manner) but about realizing specific mathematical patterns.

Of course. The Universe speaks to us through symbols. There is no universal language, humanity has not invented it despite the multitude of nations and languages. Languages were invented by humanity, and there are so many surprising similarities between them around the world. Makes you think. But the main language of the Universe is mathematics, numeral symbols. If we take the works of the ancient masters, we’ll discover they’re all based on symbols, they all have messages to impart.

Your photos are very colorful. They’re so... Take for example your black and white photos, they’re so fine. Photos are about light and color, about these rhythms…

Yes, “rhythm” is the correct word. I frequently start with the idea that everything in our world moves, everything vibrates with specific frequencies. It’s all down to each object’s vibration frequency. A stone also vibrates, just with its own frequency. Everything in the world moves and vibrates, quantum physics talks about that. Everything moves internally at the level of particles, atoms. An electron flies with the speed of light even inside an atom. Thus, everything moves and vibrates. It’s just that the frequencies are different.

What other movements, philosophers, scientists, and writers had an impact on you? Name the most important auteurs whose work helps you to develop as an artist and researcher.

I was an avid reader since the Soviet period when literature had to be reprinted, even rewritten by hand… I remember this because my mother read and left me her books. My favorite authors include Hermann, Thomas Mann, and, as strange as it sounds, Oscar Wilde. I think that Wilde lived and tragically died as an artist. Yes, we shouldn’t idealize people, but I do have a literal ideal in front of whom I prostrate myself: Andrei Tarkovksy. Because I see myself in each of his utterances, in each of his words. I don’t know. I have his “Martyrology,” a bedside book, a book for all times. If we’re talking about poetry, then I have to note Arseny Tarkovsky. Sergei Yesenin is also close to my heart.

My favorite books include “The Picture of Dorian Gray.” “A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man” by James Joyce is another favorite. And also “Steppenwolf” with its protagonist Harry Haller with whom I identify. I read the novel when I was 17 while thinking about my purpose. Literature where heroes oppose the society in some way always resonated with me.

If we’re talking about the way you relate to the world, audiences, collectors, art lovers, and our contemporaries in general, is contact with the viewer important to you?

Perhaps, this will shock you, but money is unimportant for me. I always say that I don’t paint for money. I can’t help but paint, and even if I won’t exhibit anything I’ll still paint. It’s an internal need, and I understand what I have to do to share myself with the world. Contact with people is paramount for me. And it doesn’t matter to me whether the person is an important art critic or a cleaner at the gallery where I exhibit my work. You won’t believe it, but my greatest fan, a real top fan, is a woman whom I never even saw. Her name is Lyubov, she’s a director of a kindergarten in Taganrog. She understands my paintings so well, I never met an art lover who would be able to comment and appreciate my art as her. She writes every time a post a piece on Facebook and explains her vision of each painting. And this brings me so much joy. Lyubov is seemingly from a different milieu, she’s about 70. And yet she has a very fine understanding of me. But we sometimes interact with different people of diverging levels. It’s very important for me to see actual paintings in front of me because in real life they can appear completely different. The same thing happened with Alisher Usmanov, who bought his first painting by photo. And when it was delivered to him and he saw it he proceeded to order two more.

My paintings have a prominent relief, I even discussed this with my friends involved in perception research. We’re actually thinking about doing an exhibition for people with vision matters. I would be very interested in understanding what they would be able to “see” by touching my paintings: something figurative or something abstract.

But I do think that the thousands of words we spoke won’t explain it all. Art lovers must come and view your work on their own.

Curator: Marina Fedorovskaya

Artist:

Alexandre Beridze